Shelter killing is the leading cause of death for healthy dogs and cats in the United States. Three to four million of them. Did you know that? I didn’t. Here’s another one I hadn’t considered. What if everything the major animal advocacy groups have been telling us for years about why animals are killed in American shelters is wrong? What if pet overpopulation, the main reason those organizations give for the killing, doesn’t really exist? I was invited to a screening of Nathan Winograd’s new film, Redemption: The No Kill Revolution in America, based on his award-winning book of the same name. It was a must see film event, also attended by New York City’s Deputy Mayor, the Deputy Health Commissioner, the City shelter director, and the shelter’s veterinarian. What I learned was so important and compelling to those of us who love animals, I have to share it with you. But first, you’ll need some background for context. Stick with me; it’s a long post, in two parts. But, I promise what you learn will change the way you view the shelter system and the major protection groups we’ve come to know and trust.

The beginnings of animal advocacy

The driver of a cart laden with coal is whipping his horse. Passersby on the New York City street stop to gawk not so much at the weak, emaciated equine, but at the tall man, elegant in top hat and spats, who is explaining to the driver that it is now against the law to beat one’s animal. Thus, America first encounters “The Great Meddler.” (courtesy of the ASPCA website). That Great Meddler was Henry Bergh, an aristocratic animal lover who, months before, had witnessed a disturbing display of animal cruelty towards another cart horse. He made it his mission to marshall the forces of his formidable influence with the sole purpose of creating laws to protect animals.

On February 8, 1866, during a New York City blizzard, Bergh persuaded 100 in a roomful of influencers, including the Mayor, to sign his Declaration of the Rights of Animals, pledging themselves to suppressing cruelty and showing mercy to animals. And with that, the ASPCA was born. For over two decades, Bergh spent each night tending to sick animals and hauling drivers who overworked them off to the local justice for prosecution on charges of cruelty. Within two years of the ASPCA’s incorporation, limits on passengers were common, horses were better cared for, and water troughs and buckets for thirsty horses could be seen throughout the city.

He labored equally hard for the city’s stray dog population, particularly against abuses at the hands of the city dogcatchers, who doled out unspeakable cruelty to the hundreds of dogs they captured and killed each day. Before his death in March of 1888, Henry Bergh said, “I hate to think what will befall this Society when I am gone.” He couldn’t have been more right. Against his express instructions, the ASPCA traded in its mission of protecting animals from harm for the role of killing them by agreeing to run the dog pound. For the next 150 years, the “pound” would employ the “rampant kill” philosophy, with the excuse that there just weren’t enough homes for all of the stray animals.

Who is Nathan Winograd?

To appreciate his position and what’s he’s accomplished, you need to know something about who Nathan Winograd is. First and foremost, Nathan is an animal lover. Like us, it broke his heart to hear about animals being abused or being killed in shelters. He firmly believes all living beings have a right to live Because of his love for animals, Nathan has worked in the animal protection movement for over 20 years. He’s got some impressive credentials, too. He’s a graduate of Stanford Law School, an attorney and former criminal prosecutor, and has held a variety of leadership positions including director of operations for the San Francisco SPCA and executive director of the Tompkins County SPCA, two of the most successful shelters in the nation. Under his leadership, Tompkins County, New York, became the first No Kill community in the U.S.

He has also spoken nationally and internationally on animal sheltering issues, has written animal protection legislation at the state and national level, has created successful No Kill programs in both urban and rural communities, and has consulted with a wide range of animal protection groups, including some of the largest and best known in the nation. He is the author of four books, Redemption, Irreconcilable Differences, All American Vegan and Friendly Fire (the latter two co-written with his wife, Jennifer).

Redemption sold over 100,000 copies (he also gave thousands away, in addition), won five national book awards and is considered the most acclaimed book on animal shelters ever written. Not bad for a book one publisher said would never find an audience or sell. Nathan is also the director of the No Kill Advocacy Center. He has been an ethical vegan for over 20 years, writes a vegan blog, and has written a vegan cookbook. He and Jennifer are raising two vegan kids and a vegan dog. Wow!

Read on to learn why shelters do kill and how to end it, once and for all.

Why do shelters kill?

Before the birth of the No Kill movement and the publication of Winograd’s book, Redemption, the prevalent logic, circular as it may have been, was that shelters killed because they had to. The argument was that the American public were uncaring and irresponsible in abandoning their pets or not adopting enough pets, and there were just too many animals and not enough homes for them. If we don’t kill, they said, how can we care for so many animals? And for a very long time, we lamented it, but we believed them.

Already involved in the animal protection movement for many years, it took a meeting with his future wife, Jennifer, for Nathan Winograd to question that belief, too. Jennifer argued that, even if it was true that pet overpopulation existed, if we simply refused to do it, it would end. And, as animal activists, it was their jobs to find alternatives. She also asked Nathan a key question he’d never considered. How did he know that pet overpopulation was real? Winograd, a Stanford law student at the time, with a 4.0 department GPA, high honors in Political Science, his Phi Beta Kappa and Summa Cum Laude, came face to face with what he called “my own sloppy logic and slipshod thinking about the issue.”

And, that began a journey that started in San Francisco, then Tompkins County, New York, and visiting hundreds of shelters across the country, only to discover that his first hand experiences didn’t conform to these assumed beliefs. Animals were not being killed as a last resort, but the first one. Killing was easy and convenient, so shelter directors made no effort to come up with alternatives. And, no one was holding them accountable for it. Shelters are able to kill 80% of the animals, and no one’s looking to replace them.

“In shelter after shelter, I would find animals being killed so that cages did not have to be cleaned and the animals inside them wouldn’t have to be fed, sparing staff the effort of doing the job they were being paid by the public to perform,” explained Winograd. “In shelter after shelter, I found empty cages, sometimes banks and banks of them.

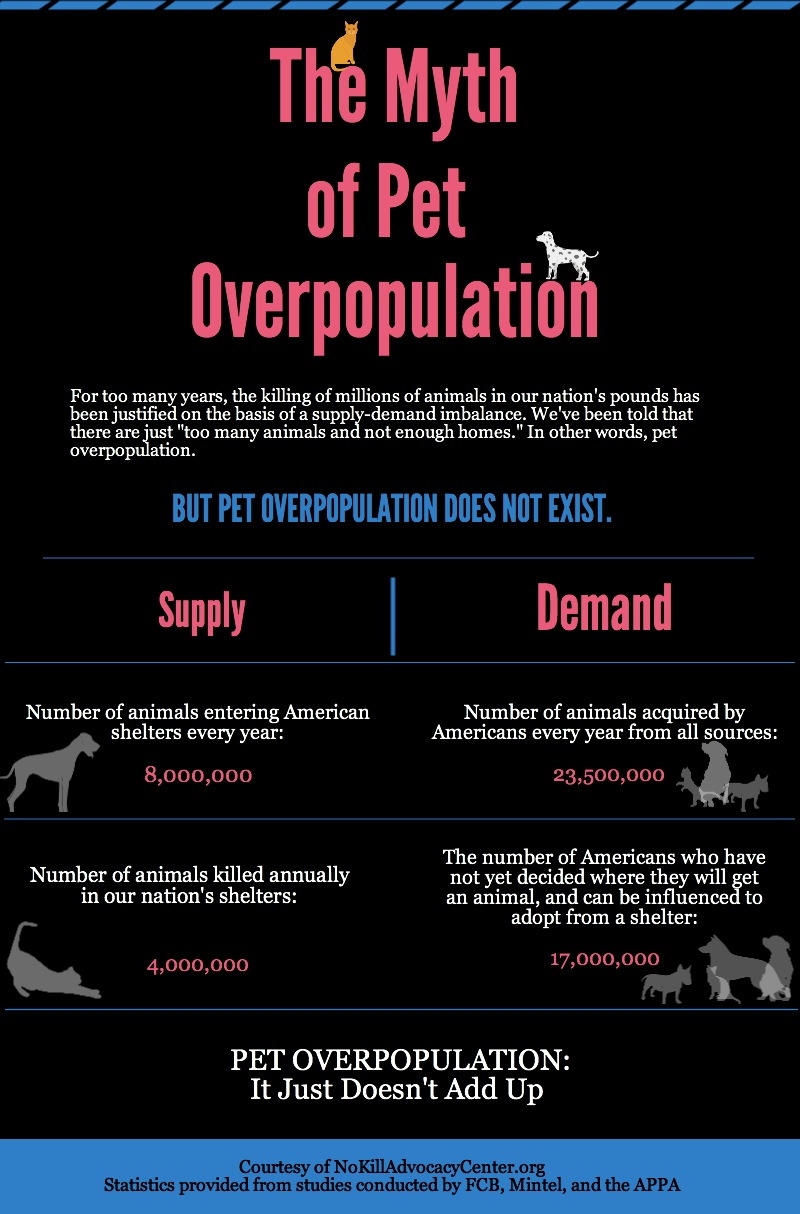

“So, I began reviewing data…on animals intakes and studies on available homes.” Nathan studied the data on over 1,000 shelters nationwide, from states that mandate shelter reporting, comparing it with national studies on birth, death and acquisition rates for companion animals. The conclusion became crystal clear: the number of homes in America vastly exceeds the number of shelter animals in need of a home. Here are the surprising numbers he discovered.

What is the data he found?

* 8 million animals end up in American shelters each year, but only 65% of total intakes actually need homes. Why? Some animals, like community cats who are not socialized to people, need neuter and release. Others will be—and many more can be with greater effort—reclaimed by their families. Still others are irremediably suffering or hopelessly ill. And many more can be kept out of the shelter through a comprehensive retention effort, helping people overcome the challenges which have caused them to seek the surrender of their animal companion to the local shelter in the first place. In truth, shelters only need to find homes for a high end of 65% of total intakes.

* 3-4 million are killed each year in American shelters, 2.7 million of them for lack of new home.

* The data suggests from the most successful adoption communities, that U.S. shelters combined have the potential to adopt almost 9 million pets a year, three times the number being killed for lack of a home.

* 23.5 million Americans get an animal each year

* 17 million of them are undecided as to where to get one from and can be influenced to adopt from a shelter

* 17 million people vying for 3 million animals. Even if 80% of those 17 million acquired from someplace other than a shelter, we can still zero out the killing.

It’s a matter of supply and demand. With 2.7 million animals being killed, but for a home annually (supply), and the data of how many Americans acquire a pet, either for the first time, as a replacement for a deceased pet or to add to their pet family (low end of 9.1 million to high end of 37.3 million annually (demand), the calculus isn’t even close! The number of people looking to acquire an animal is so much larger than the shelter “supply.” (data courtesy of the nokilladvocacycenter.org website)

Once Winograd understood this, he and Jennifer’s goal became creating no kill communities, where no shelters in that community kills. But, he came across incredible pushback. Even though one would assume those in the business of protecting animals would automatically want to save lives and jump at the chance to do so, that’s not what Nathan experienced. No Kill fell not only on deaf ears, but defiant ones. Organizations like the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), the ASPCA and the American Humane Association (AHA) weren’t interested in reform. They didn’t need to be. They’d grown large, wealthy and powerful by lamenting the killing but not rocking the boat. Relationships with their friends and colleagues at shelters and other organizations were also at stake. Over time, they’ve become lobbyist for kill shelters, instead of the mission they were created to do. Even PETA tried to discredit and stop Winograd at every turn. I’ve been a big PETA supporter for years; I always felt they got the job done bringing attention to lab animals, the fur trade and animal farming. But, I learn PETA is a big believer in killing companion animals in shelters. They’ve killed close to 30,000 of them in the last 11 years! Here’s a sample of what Nathan encountered, this from PETA:

“The dangerous, unrealistic policies and procedures pushed on the council by this small but fanatical constituency is part of a national movement to target, harass, and vilify open admission shelters and their staff in an effort to mislead the public into believing that ‘no kill’ is as easy as simply not euthanizing animals… [Quoting HSUS:] ‘There are no municipal shelters in the country that operate as ‘no-kill.’ A few have tried, but have quickly turned back due to overcrowding, inability to manage services, and staff outcry. It is the municipality’s job to accept all animals and conduct responsible adoptions. The reality is there are not enough homes for all animals…’ The goals of reducing overpopulation and euthanasia do not get accomplished by limiting yourself to the category of ‘no-kill.’ It is an unattainable goal that will set you up for failure.” Daphna Nachminovitch, PETA Vice-President, Cruelty Investigations Department, Letter to the Mayor of Norfolk, Virginia.

So what did he do when the animal protection community didn’t want change? He realized the way to evoke reform was through community animal lovers, like you and me. We weren’t the ones who needed to change, even though the large animal protection groups complained we were. The shelters had to change. Nathan went inside, beginning as the Director of Law and Advocacy, then Director of Operations and then Vice President of the San Francisco SPCA, and then as Executive Director of New York’s Thompson County shelter, where he implemented and then expanded upon the SF/SPCA model of saving lives, getting the local communities involved. It wasn’t without its challenges; no one had taken a full-service open admission shelter and operated it as a No Kill shelter. But, with a committee of some of the most respected veterinarians in the country and a lot of guts, not only did it work, but it worked in record time. Killing was reduced by 75%, and disease rates and death in kennel rates by 90% from the model he inherited. Find out how he did it in Part Two, tomorrow.

Purchase Redemption: The Myth of Pet Overpopulation and the No Kill Movement in America

Does your local shelter kill animals? Find out what you can do in Part Two, tomorrow.

(Disclaimer: affiliate links)