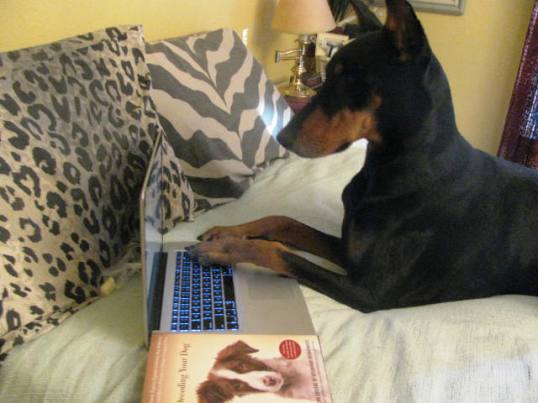

Destroying the house when you’re out; incessant barking in the crate; lunging at people; barking at people…do any of these sound like your dog? I can put “Check!” next to a few. Today’s post is the final one in a three-part series on dog behaviors explained by the experts. We’ll tackling some of the tough stuff – separation anxiety and how you know if your dog has it; fear-agression issues and what that means. We even have some great advice for moms and dads of senior dogs, to help them stay sharp and healthier, longer. A new book, Decoding Your Dog, written by American College of Veterinary Behaviorists-certified vets, Drs. Debra Horwitz and John Ciribissi, is a great tool to get answers on these and many other topics. I talked to Dr. Horwitz to get additional insight for us on some common behavior issues. We are being challenged everyday with our new rescue dog, Jasper, who has separation anxiety and fear-based aggression. I’ve included some of our story, in the hopes some of my readers can relate, and that the advice will help them, too. Here’s the second, and last, part of that interview.

Separation anxiety

Jasper has separation anxiety, so he can’t be crated or put behind a baby gate. We tried and it was awful for all of us. And, we aren’t going to leave Sophie, our four-year-old dog, and Jasper alone together for a while. We just don’t know him well enough, and we want to protect both of them from getting hurt. So, our lives have literally been turned upside down over the past month, since the little guy came here to live. Basically, we don’t have a life. Going out has become a tactical operation, worthy of the Department of Defense. Finding out we have a 10-month old puppy, when Animal Care and Control told us we were adopting a four year old adult dog, didn’t help, either. It poses unexpected challenges of house training, unpredictable behavior and different energy levels between the two dogs. We did buy two small video cameras, so we could see what they do when they are alone for a couple of minutes, while we’re downstairs in our lobby. Just to know.

Some readers may also have dogs with separation anxiety who can’t go into a crate. What do you do? Here’s what Dr. Horwitz had to say.

BaS: If we have a dog that is fearful of enclosed spaces, for example, the crate, how do we deal with that? Is getting them used to it in ever increasing increments or is biting the bullet and letting them howl it out the way to go? How would that affect the human/animal bond?

DDH: A dog that seems to be distressed about being in enclosed spaces may suffer from separation anxiety. If that’s the case, you aren’t going to be able to make them ok about being home alone or in the crate without treatment. Some people put their dogs in a crate because they’re destructive in the house or for house training purposes. So, you first have to determine why the dog won’t go into the crate. Some dogs feel very frightened to be confined in that way. You can teach dogs to be in their crate, if they don’t have separation anxiety or fear of being in a locked space, by making it a fun place to be. Put great toys and treats in there, bully sticks. Close the door, count to 20, let the dog out. Let the dog realize it’s a safe place to be, whether the door’s open or closed, whether you’re home or gone. And there are a huge number of dogs who do fine in a crate.

BaS: How can we tell if our dog really has separation anxiety?

DDH: Commonly, when a dog has separation anxiety, they bark, they howl, they whine, they urinate or defecate and are destructive while in the crate or while home alone. They may bite at the crate bars or move it around the room. My first question to a client with this situation would be, ‘Why are you crating your dog?’

But, there are other dogs who are immobile the entire time the owner is out. They’re not sleeping. They, too, might be suffering from separation anxiety. It’s always a good idea to video your dogs while you’re gone. You can’t know what your dog does when you’re not home, unless you video them. If you have any doubts about what you’re seeing after viewing it, you should take it to your vet, who can tell you.

BaS: The book talks about how some behavior issues may be associated with a serotonin dysfunction in the brain. Is there a test for this?

DDH: There isn’t any general test for this. It’s a very sophisticated test to look at their cerebral spinal fluid to determine if there’s a low level of serotonin. However, we do use serotonin enhancing drugs for the same reasons they might be used in people, when we have extreme impulsivity or we have extreme anxiety that makes it very difficult for the dog to learn. They can’t focus on what you’re trying to teach them because they’re so afraid of everything in their environment. All they can see is danger on all sides. We need to turn that down a little. Medications like these can only be prescribed by a veterinarian or a veterinary behaviorist.

Fear-based aggression

I explained to Dr. Horwitz about the challenges we have with Jasper. Getting him in and out of our apartment is very stressful because he’s so unpredictable. If the elevator door opens, and someone is inside, Jasper will go off, shriek barking and lunging. Age, gender, color, he doesn’t discriminate. We can’t go into an occupied elevator with him. Living in an apartment building in NYC, that poses a big challenge. So, we wait for an empty elevator. The next challenge is getting him through the lobby, without an incident. His triggers are strangers, some other dogs, children, anything, really. And, he can be the same way on the actual walk. We have some good days and some bad days. He was making huge strides around his walks, even though we were still having a hard time with the elevator and lobby, and then all of a sudden, for two days in a row, he was in the red zone all the time outside. We just don’t know, and it’s breaking our hearts to think we may not be able to handle this long term. If we lived in the country, it might be easier because there wouldn’t be so much stimulation. So, I was welcoming any insight Dr. Horwitz might provide for us and readers who also have dogs grappling with fear aggression.

Tip: One tip from Dr. Horwitz that we are trying is using pheromones on Jasper. She told me about a product called Adaptil, which is a copy of the pheromone secreted by the mammary glands of nursing dogs. It comes in a diffuser for the home, as a collar for the dog and as a spray. She said it works well on some anxious or nervous dogs. If you get the collar, it needs to be against the skin. They get activated through the dog’s pores, so you need to make sure there’s just enough room for one finger to slip in between it and the dog’s neck. You can get Adaptil through your vet or online. You take the collar off when you’re giving the dog a bath, as it can’t get wet. The collar remains active for about one month. She said that, in addition to the training we’re already doing with Jasper, it can cut their nervousness enough, so that he might still be moderately reactive when you step into an occupied elevator (or if you step away from one), but he can return to baseline more quickly. I’ll let you know how this works. We just received ours yesterday.

BaS: You talk about the concept of having our dog’s back. Can you explain?

DDH: Let’s take the case of the elevator, but it could be any trigger that feels threatening to your dog. If the elevator door opens with someone inside, you can turn your back on the threat, literally, and even say a key phrase to your dog like, ‘We’re not going.’ You’d move away from the threat, wait until he visibly calms down and then return to the elevator. After repeating this for a bit, he begins to associate ‘We’re not going,’ with you having his back, taking care of the threat so he doesn’t have to be exposed to it. In time, you may even be able to get into the elevator, and saying ‘We’re not going’ will be enough. It calms him right away because he understands the communication tools between the two of you.

One of the things we talk about in the book is having a language system with your dog, so they feel safe. You can’t only do that verbally because, until they learn what those words mean, they won’t understand. Cue that word with an action that makes them feel safe, then they get that you’re going to take care of them and ‘have their back.’

BaS: Do you have best techniques of how people should deal with different kinds of fear aggression, i.e.: a dog fearful of their owner; of strangers; of other dogs?

DDH: I’ll answer that in two parts. There are some dogs who are universally afraid of a lot of things. Maybe that’s because they have a fearful personality. Then, we have dogs who have very specific triggers. Hopefully, the vet’s history taking is going to help differentiate between the two. If there’s a specific trigger, that’s what the dog has to learn is ok. If there are a number of triggers, that may require a different approach. That being said, there are some general recommendations we make for dogs who are fearful, which are somewhat similar across the board. If a dog is fearful of strangers, we tell people to not put their dog into that situation, where you’re exposing him at a level you cannot control.

BaS: That’s not always possible, though.

DDH: It’s not, but it is more possible than you think. If you’re someone who works from home, maybe you choose a time of day to walk your dog when the likelihood of him encountering a lot of strangers is less, so he’s not as afraid. Instead of walking him between 7 – 9am, when most people will be leaving for work, maybe walk him between 5-7am or 9-11am. He has to go for walks, but if you can minimize his exposure to that which makes him the most afraid, over time, he can learn that sometimes he can do this and it’s ok. You want to avoid the trigger, and put as much distance between the dog and the trigger as possible. And that’s true for all fear anxiety issues.

Advice for seniors

Many of us have been through it. Time marches on and our active young dogs evolve into slower moving seniors. Today, there are tools we have at our disposal to help slow the onset of senior symptoms. Advances in veterinary care, nutrition, and behavioral care mean many dogs are living longer lives. There’s a chapter dedicated to seniors and, one of the topics is about CDS (cognitive dysfunction syndrome), a kind of canine Alzheimers that some dogs develop with age. Signs of CDS in dogs are known by an acronym called DISHA. Here’s what we should be watching out for in our senior dogs:

- D: disorientation

- I: changes in social interactions

- S: changes in sleep-wake cycles

- H: house soiling

- A: changes in activity levels

They also say anxiety or agitation may be signs of CDS, but it is important to rule out other causes with your vet, before you determine it’s CDS, especially in seniors where other health issues can be impacting behavior.

BaS: When it comes to CDS, when is it best for us, as owners, to intervene? And, are the cost of these medications or supplements prohibitive or manageable for most of us?

DDH: Cost depends on what interventions you choose and at what level your dog needs them. I told you about my dog, Oscar. What I didn’t tell you is he’s 14 and a half. He’s on nutritional supplements; he gets one tablet a day. The cost can vary between .50 and $1.00 a day. Some dogs need to be on multiple supplements. There are also foods available that maybe, on a per day basis, are a little bit more expensive, but they do help. What I think is important when we do talk about CDS, is that if people are on the lookout for symptoms of aging and get them on these supplements early in the process, I think what’s going to happen is you’re going to slow down the decline.

With a senior dog, we want to maximize the quality of life. When it comes to CDS, early intervention with these products seem to really make a difference at increasing that quality of life and in their ability to stay young and pretty healthy. We don’t really have tests to identify CDS, but we talk to owners. One of the first signs is what I like to call ‘the dead dog sleep,’ where you come home and your dog’s sacked out and doesn’t even hear you come in. At the first sign of that, it might be the time to start the supplements, because the dog is not as sharp. You can increase alertness, just as you can with humans, by having the right supplements onboard. So, don’t wait until the dog is so out of it that he’s urinating in the house. When you see that you’ve got to call his name six times, before he goes, ‘Huh? You talkin’ to me?’, that’s a sign that it’s time to intervene. Your vet can help you choose what supplements are right for your particular dog.

In summary

I learned so much reading Decoding Your Dog. It’s given me a framework for working with a local behaviorist for Jasper, and I now feel like I have a bit of a foundation in the issues we’re hoping to find solutions for.

I love my animals, like you. I want to do the right thing for them and sometimes, it’s not easy to know what that is, especially when it comes to behavior problems. You can see we’re struggling with trying to fit Jasper into our lives, where it works for everyone. And, I’ll continue to write about our challenges and our triumphs with him. But, having a book like Decoding Your Dog is a tool I can trust and will use.

For those who want to purchase the book, you can find it here.

Patricial McConnell, PhD and author of many renowned books on dog training and behavior, said it well. “Kudos to the Veterinary Behaviorists! Decoding Your Dog is a welcome addition to the voices supporting science-based and benevolent dog training. Read this book and your dog will thank you for it!”

Do you have a particular behavior problem with your dog? What is it and how are you dealing with it? Tell me about it in the comments.

(Disclaimer: affiliate links)